Ch4 Lecture 2

More Least Squares

Normal equations for multiple predictors

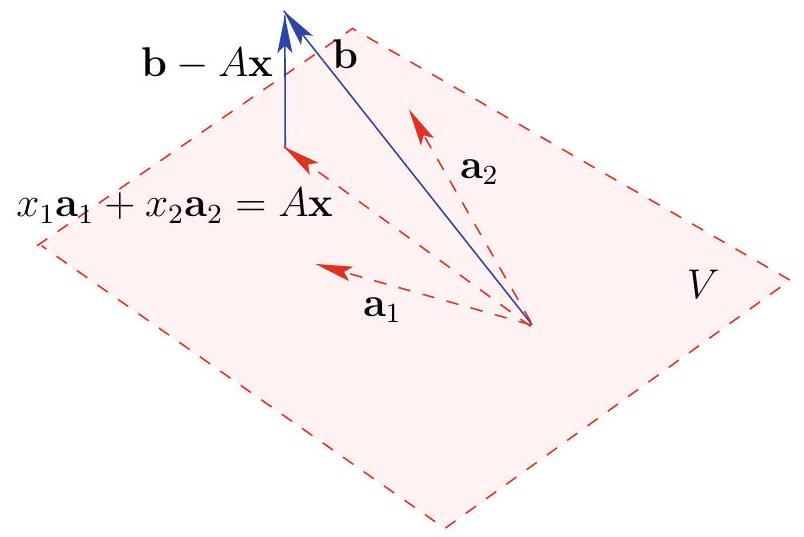

When we have multiple predictors, \mathbf{A} is a matrix

Each column corresponds to a predictor variable.

\mathbf{x} is a column vector of the coefficients we are trying to find, one per predictor.

What do the normal equations tell us? We can break them apart into one equation corresponding to each column of \mathbf{A}.

\begin{aligned} \mathbf{A}^{T} \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} &=\mathbf{A}^{T} \mathbf{b} \\ \text{becomes} \\ \mathbf{a_i}\cdot \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} &=\mathbf{a_i} \cdot \mathbf{b}\text{ for every i} \\ \mathbf{a_i}\cdot \left(\mathbf{b}-\mathbf{Ax}\right)&=0\text{ for every i} \end{aligned}

We need to find \mathbf{x} such that the residuals are orthogonal to every column of \mathbf{A}.

Example

We have two predictors a_1 and a_2 and a response variable b. We have the following data:

| x_1 | x_2 | y |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

We are hoping to find a linear relationship of the form \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 = y for some values of \beta_1 and \beta_2.

This would bring us the following system of equations:

\begin{aligned} 2 \beta_{1}+\beta_{2} & =0 \\ \beta_{1}+\beta_{2} & =0 \\ 2 \beta_{1}+\beta_{2} & =2 . \end{aligned}

Obviously inconsistent! (2 \beta_{1}+\beta_{2} cannot equal both 0 and 2.)

Find the least squares solution using the normal equations:

Change variable names, so the \betas are now \mathbf{x}, the xs are now the columns \mathbf{A}, and the ys are now \mathbf{b}.

A=\left[\begin{array}{ll} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 \end{array}\right], \text { and } \mathbf{b}=\left[\begin{array}{l} 0 \\ 0 \\ 2 \end{array}\right]

Residuals are \mathbf{b}-\mathbf{A} \mathbf{x}.

Normal equations are \mathbf{A}^{T} \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x}=\mathbf{A}^{T} \mathbf{b}.

A^{T} A=\left[\begin{array}{lll} 2 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ll} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ll} 9 & 5 \\ 5 & 3 \end{array}\right]

with inverse \left(A^{T} A\right)^{-1}=\left[\begin{array}{ll} 9 & 5 \\ 5 & 3 \end{array}\right]^{-1}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{rr} 3 & -5 \\ -5 & 9 \end{array}\right]

A^{T} \mathbf{b}=\left[\begin{array}{lll} 2 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{l} 0 \\ 0 \\ 2 \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{l} 4 \\ 2 \end{array}\right]

Least Squares Solution

\mathbf{x}=\left(A^{T} A\right)^{-1} A^{T} \mathbf{b}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{rr} 3 & -5 \\ -5 & 9 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{l} 4 \\ 2 \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{r} 1 \\ -1 \end{array}\right]

Back in our original variables, this means the best fit estimate for \beta_1 is 1 and the best \beta_2 is -1.

Orthogonal and Orthonormal Sets

The set of vectors \mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{n} is an orthogonal set if \mathbf{v}_{i} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{j}=0 whenever i \neq j.

If, in addition, each vector has unit length, i.e., \mathbf{v}_{i} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{i}=1, then the set of vectors is orthonormal .

Orthogonal Coordinates Theorem

If \mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{n} are nonzero and orthogonal, and

\mathbf{v} \in \operatorname{span}\left\{\mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{n}\right\},

\mathbf{v} can be expressed uniquely (up to order) as a linear combination of \mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{n}, namely

\mathbf{v}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}+\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2}+\cdots+\frac{\mathbf{v}_{n} \cdot \mathbf{v}}{\mathbf{v}_{n} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{n}} \mathbf{v}_{n}

Proof

Since \mathbf{v} \in \operatorname{span}\left\{\mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{n}\right\},

we can write \mathbf{v} as a linear combination of the \mathbf{v}_{i} ’s:

\mathbf{v}=c_{1} \mathbf{v}_{1}+c_{2} \mathbf{v}_{2}+\cdots+c_{n} \mathbf{v}_{n}

Now take the inner product of both sides with \mathbf{v}_{k}:

Since \mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{j}=0 if j \neq k,

\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v} & =\mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot\left(c_{1} \mathbf{v}_{1}+c_{2} \mathbf{v}_{2}+\ldots \cdots+c_{n} \mathbf{v}_{n}\right) \\ & =c_{1} \mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}+c_{2} \mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}+\cdots+c_{n} \mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{n}=c_{k} \mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{k} \end{aligned}

Since \mathbf{v}_{k} \neq 0, \left\|\mathbf{v}_{k}\right\|^{2}=\mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{k} \neq 0 so we can divide::

c_{k}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}}{\mathbf{v}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{k}}

Any linear combination of an orthogonal set of nonzero vectors is the sum of its projections in the direction of each vector in the set.

Orthogonal matrix

Suppose \mathbf{u}_{1}, \mathbf{u}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{u}_{n} is an orthonormal basis of \mathbb{R}^{n}

Make these the column vectors of \mathbf{A}: A=\left[\mathbf{u}_{1}, \mathbf{u}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{u}_{n}\right]

Because the \mathbf{u}_{i} are orthonormal, \mathbf{u}_{i}^{T} \mathbf{u}_{j}=\delta_{i j}

Use this to calculate A^{T} A.

- its (i, j) th entry is \mathbf{u}_{n}^{T} \mathbf{u}_{n}

- = \delta_{i j}

- So we have = A^{T} A=\left[\delta_{i j}\right]=I

- Therefore, A^{T} = A^{-1}

Orthogonal matrix

A square real matrix Q is called orthogonal if Q^{T}=Q^{-1}.

A square matrix U is called unitary if U^{*}=U^{-1}.

Example

Show that the matrix R(\theta)=\left[\begin{array}{rr}\cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta\end{array}\right] is orthogonal.

\begin{aligned} R(\theta)^{T} R(\theta) & =\left(\left[\begin{array}{cc} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{array}\right]\right)^{T}\left[\begin{array}{cc} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{array}\right] \\ & =\left[\begin{array}{cc} \cos \theta \sin \theta \\ -\sin \theta \cos \theta \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cc} \cos \theta-\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{array}\right] \\ & =\left[\begin{array}{cc} \cos ^{2} \theta+\sin ^{2} \theta & \cos \theta \sin \theta-\sin \theta \cos \theta \\ -\cos \theta \sin \theta+\sin \theta \cos \theta & \sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ll} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{array}\right], \end{aligned}

Rigidity of orthogonal (and unitary) matrices

This rotation matrix preserves vector lengths and angles between vectors (illustrate by hand).

Thus, R(\theta)\mathbf{x}\cdot R(\theta)\mathbf{y}=\mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{y}

This is true in general for orthogonal matrices:

Q \mathbf{x} \cdot Q \mathbf{y}=(Q \mathbf{x})^{T} Q \mathbf{y}=\mathbf{x}^{T} Q^{T} Q \mathbf{y}=\mathbf{x}^{T} \mathbf{y}=\mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{y}

also,

\|Q \mathbf{x}\|^{2}=Q \mathbf{x} \cdot Q \mathbf{x}=(Q \mathbf{x})^{T} Q \mathbf{x}=\mathbf{x}^{T} Q^{T} Q \mathbf{x}=\mathbf{x}^{T} \mathbf{x}=\|\mathbf{x}\|^{2}

Finding orthogonal bases

Gram-Schmidt Algorithm

Let \mathbf{w}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{w}_{n} be linearly independent vectors in a standard space.

Define vectors \mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{n} recursively:

Take each \mathbf{w}_{k} and subtract off the projection of \mathbf{w}_{k} onto each of the previous vectors \mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{k-1}

\mathbf{v}_{k}=\mathbf{w}_{k}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{k}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{k}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2}-\cdots-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{k-1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{k}}{\mathbf{v}_{k-1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{k-1}} \mathbf{v}_{k-1}, \quad k=1, \ldots, n

\mathbf{v}_{k}=\mathbf{w}_{k}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{k}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{k}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2}-\cdots-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{k-1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{k}}{\mathbf{v}_{k-1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{k-1}} \mathbf{v}_{k-1}, \quad k=1, \ldots, n

Then

The vectors \mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{k} form an orthogonal set.

For each index k=1, \ldots, n,

\operatorname{span}\left\{\mathbf{w}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{w}_{k}\right\}=\operatorname{span}\left\{\mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \ldots, \mathbf{v}_{k}\right\}

Example

Let V=\mathcal{C}(A) with the standard inner product and compute an orthonormal basis of V, where

A=\left[\begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 2 & 0 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & 3 & 2 \\ 1 & -1 & 3 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & -3 & 1 \end{array}\right]

RREF of A is:

R=\left[\begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 0 & 2 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array}\right]

The independent columns are columns 1, 2, and 4.

So let these be our \mathbf{w}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}, \mathbf{w}_{3}.

Step 1: \mathbf{v}_{1}=\mathbf{w}_{1}=(1,1,1,-1)

Step 2: \mathbf{v}_{2}=\mathbf{w}_{2}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1} . . .

=(2,-1,-1,1)-\frac{-1}{4}(1,1,1,-1)=\frac{1}{4}(9,-3,-3,3)

Step 3: \mathbf{v}_{3}=\mathbf{w}_{3}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2}

=(-1,2,2,1)-\frac{2}{4}(1,1,1,-1)-\frac{-18}{108}(9,-3,-3,3)=(0,1,1,2)

Finding orthonormal basis

Now we need to normalize these vectors to get an orthonormal basis.

\mathbf{u}_{1}=\frac{1}{\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\|} \mathbf{v}_{1}=\frac{1}{2}(1,1,1,-1)

\mathbf{u}_{2}=\frac{1}{\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\|} \mathbf{v}_{2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt(108)}(9,-3,-3,3)

etc.

QR Factorization

If A is an m \times n full-column-rank matrix, then A=Q R, where the columns of the m \times n matrix Q are orthonormal vectors and the n \times n matrix R is upper triangular with nonzero diagonal entries.

Why do we care?

- Can use to solve linear systems:

- can be less susceptible to round-off error than Gauss-Jordan.

- Can be used to solve least squares problems (will show you how!)

How to find Q and R

- Start with the columns of A, A=\left[\mathbf{w}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}, \mathbf{w}_{3}\right]. (For now assume they are linearly independent.)

- Do Gram-Schmidt on the columns of A:

\begin{aligned} & \mathbf{v}_{1}=\mathbf{w}_{1} \\ & \mathbf{v}_{2}=\mathbf{w}_{2}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1} \\ & \mathbf{v}_{3}=\mathbf{w}_{3}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2} . \end{aligned}

- Solve these equations for \mathbf{w}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}, \mathbf{w}_{3}:

\begin{aligned} & \mathbf{w}_{1}=\mathbf{v}_{1} \\ & \mathbf{w}_{2}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}+\mathbf{v}_{2} \\ & \mathbf{w}_{3}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}+\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2}+\mathbf{v}_{3} . \end{aligned}

\begin{aligned} & \mathbf{w}_{1}=\mathbf{v}_{1} \\ & \mathbf{w}_{2}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}+\mathbf{v}_{2} \\ & \mathbf{w}_{3}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}+\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2}+\mathbf{v}_{3} . \end{aligned}

In matrix form, these become:

A=\left[\mathbf{w}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}, \mathbf{w}_{3}\right]=\left[\mathbf{v}_{1}, \mathbf{v}_{2}, \mathbf{v}_{3}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \\ 0 & 1 & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right]

Normalizing Q

We can normalize the columns of Q by dividing each column by its length.

Set \mathbf{q}_{j}=\mathbf{v}_{j} /\left\|\mathbf{v}_{j}\right\|..

\begin{aligned} A & =\left[\mathbf{q}_{1}, \mathbf{q}_{2}, \mathbf{q}_{3}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\| & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\| & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{3}\right\| \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \\ 0 & 1 & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2}, \mathbf{v}_{2}} \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right] \end{aligned}

\begin{aligned} & =\left[\mathbf{q}_{1}, \mathbf{q}_{2}, \mathbf{q}_{3}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\| & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\|} & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\|} \\ 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\| & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\|} \\ 0 & 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{3}\right\| \end{array}\right] . \end{aligned}

Final form

\begin{aligned} A & =\left[\mathbf{q}_{1}, \mathbf{q}_{2}, \mathbf{q}_{3}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\| & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\|} & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\|} \\ 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\| & \frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\|} \\ 0 & 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{3}\right\| \end{array}\right] \\[10pt] &= \left[\mathbf{q}_{1}, \mathbf{q}_{2}, \mathbf{q}_{3}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\| & \mathbf{q}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2} & \mathbf{q}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3} \\ 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\| & \mathbf{q}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3} \\ 0 & 0 & \left\|\mathbf{v}_{3}\right\| \end{array}\right] \end{aligned}

Example

Find the QR factorization of the matrix

A=\left[\begin{array}{rrr} 1 & 2 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & 2 \\ 1 & -1 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \end{array}\right]

We already found the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization of this matrix:

\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_{1} & =\mathbf{w}_{1}=(1,1,1,-1), \\ \mathbf{v}_{2} & =\mathbf{w}_{2}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{2}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1} \\ & =(2,-1,-1,1)-\frac{-1}{4}(1,1,1,-1)=\frac{1}{4}(9,-3,-3,3), \\ \mathbf{v}_{3} & =\mathbf{w}_{3}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{1}} \mathbf{v}_{1}-\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{w}_{3}}{\mathbf{v}_{2} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{2}} \mathbf{v}_{2} \\ & =(-1,2,2,1)-\frac{2}{4}(1,1,1,-1)-\frac{-18}{108}(9,-3,-3,3) \\ & =\frac{1}{4}(-4,8,8,4)-\frac{1}{4}(2,2,2,-2)+\frac{1}{4}(6,-2,-2,2)=(0,1,1,2) . \end{aligned}

\begin{aligned} & \mathbf{u}_{1}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{1}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\|}=\frac{1}{2}(1,1,1,-1), \\ & \mathbf{u}_{2}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{2}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\|}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{108}}(9,-3,-3,3)=\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{3}}(3,-1,-1,1), \\ & \mathbf{u}_{3}=\frac{\mathbf{v}_{3}}{\left\|\mathbf{v}_{3}\right\|}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}(0,1,1,2) . \end{aligned}

The \mathbf{u} vectors we calculated before are the \mathbf{q} vectors in the QR factorization.

\begin{gathered} \left\|\mathbf{v}_{1}\right\|=\|(1,1,1,-1)\|=2 \text { and } \mathbf{q}_{1}=\frac{1}{2}(1,1,1,-1) \\ \left\|\mathbf{v}_{2}\right\|=\left\|\frac{1}{4}(9,-3,-3,3)\right\|=\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{3} \text { and } \mathbf{q}_{2}=\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{3}}(3,-1,-1,1) \\ \left\|\mathbf{v}_{3}\right\|=\|(0,1,1,2)\|=\sqrt{6} \text { and } \mathbf{q}_{3}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}(0,1,1,2) \end{gathered}

\begin{aligned} \left\langle\mathbf{q}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{2}\right\rangle & =\frac{1}{2}(1,1,1,-1) \cdot(2,-1,-1,1)=-\frac{1}{2} \\ \left\langle\mathbf{q}_{1}, \mathbf{w}_{3}\right\rangle & =\frac{1}{2}(1,1,1,-1) \cdot(-1,2,2,1)=1 \\ \left\langle\mathbf{q}_{2}, \mathbf{w}_{3}\right\rangle & =\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{3}}(3,-1,-1,1) \cdot(-1,2,2,1)=-\sqrt{3} . \end{aligned}

A=\left[\begin{array}{rrr} 1 / 2 & 3 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 0 \\ 1 / 2 & -1 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 1 / \sqrt{6} \\ 1 / 2 & -1 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 1 / \sqrt{6} \\ -1 / 2 & 1 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 2 / \sqrt{6} \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{rrr} 2 & -1 / 2 & 1 \\ 0 & \frac{3}{2} \sqrt{3} & -\sqrt{3} \\ 0 & 0 & \sqrt{6} \end{array}\right]=Q R

Solving a linear system with QR

We would like to solve the system A \mathbf{x}=\mathbf{b}.

Q R \mathbf{x}=\mathbf{b}.

Multiply both sides by Q^{T}:

Since Q is orthogonal, Q^{T} Q=I and Q^{T} Q R \mathbf{x}=R \mathbf{x}=Q^{T} \mathbf{b}.

Suppose we have \mathbf{b}=(1,1,1,1). Then we are trying to solve

\left[\begin{array}{rrr} 2 & -1 / 2 & 1 \\ 0 & \frac{3}{2} \sqrt{3} & -\sqrt{3} \\ 0 & 0 & \sqrt{6} \end{array}\right]\mathbf{x}=\left[\begin{array}{rrr} 1 / 2 & 3 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 0 \\ 1 / 2 & -1 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 1 / \sqrt{6} \\ 1 / 2 & -1 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 1 / \sqrt{6} \\ -1 / 2 & 1 /(2 \sqrt{3}) & 2 / \sqrt{6} \end{array}\right]^T \left[\begin{array}{rrr}1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array}\right]

import sympy as sp

Q = sp.Matrix([[1/2, 3/(2*sp.sqrt(3)), 0], [1/2, -1/(2*sp.sqrt(3)), 1/sp.sqrt(6)], [1/2, -1/(2*sp.sqrt(3)), 1/sp.sqrt(6)], [-1/2, 1/(2*sp.sqrt(3)), 2/sp.sqrt(6)]])

R = sp.Matrix([[2, -1/2, 1], [0, 3*sp.sqrt(3)/2, -sp.sqrt(3)], [0, 0, sp.sqrt(6)]])

b = sp.Matrix([1, 1, 1, 1])

print('$$\n Q^T b ='+sp.latex(Q.T*b)+'\n$$')

print('$$\n '+sp.latex(R)+' \mathbf{x} ='+sp.latex(Q.T*b)+'\n$$')Q^T b =\left[\begin{matrix}1.0\\\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}\\\frac{2 \sqrt{6}}{3}\end{matrix}\right] \left[\begin{matrix}2 & -0.5 & 1\\0 & \frac{3 \sqrt{3}}{2} & - \sqrt{3}\\0 & 0 & \sqrt{6}\end{matrix}\right] \mathbf{x} =\left[\begin{matrix}1.0\\\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}\\\frac{2 \sqrt{6}}{3}\end{matrix}\right]

Find \mathbf{x}=\left[\begin{array}{l} 1 / 3 \\ 2 / 3 \\ 2 / 3 \end{array}\right]

Check:

\mathbf{r}=\mathbf{b}-A \mathbf{x}=\left[\begin{array}{l} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{array}\right]-\left[\begin{array}{rrr} 1 & 2 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & 2 \\ 1 & -1 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{l} 1 / 3 \\ 2 / 3 \\ 2 / 3 \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{l} 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array}\right] .

Least Squares with QR factorization

What if we have a system that’s not consistent?

pause

The QR factorization can be used to solve the least squares problem A \mathbf{x} \approx \mathbf{b}.

Haar Wavelet Transform

Image compression idea

Haaar wavelet transform

In 1D, N data points \left\{x_{k}\right\}_{k=1}^{N}

Can average terms:

y_{k}=\frac{1}{2}\left(x_{k}+x_{k-1}\right), \quad k \in \mathbb{Z}

At the same time, we can apply a difference filter (“unsmoothing”):

z_{k}=\frac{1}{2}\left(x_{k}-x_{k-1}\right), \quad k=1, \ldots, N

Idea: take our data, apply both filters to it and keep the results.

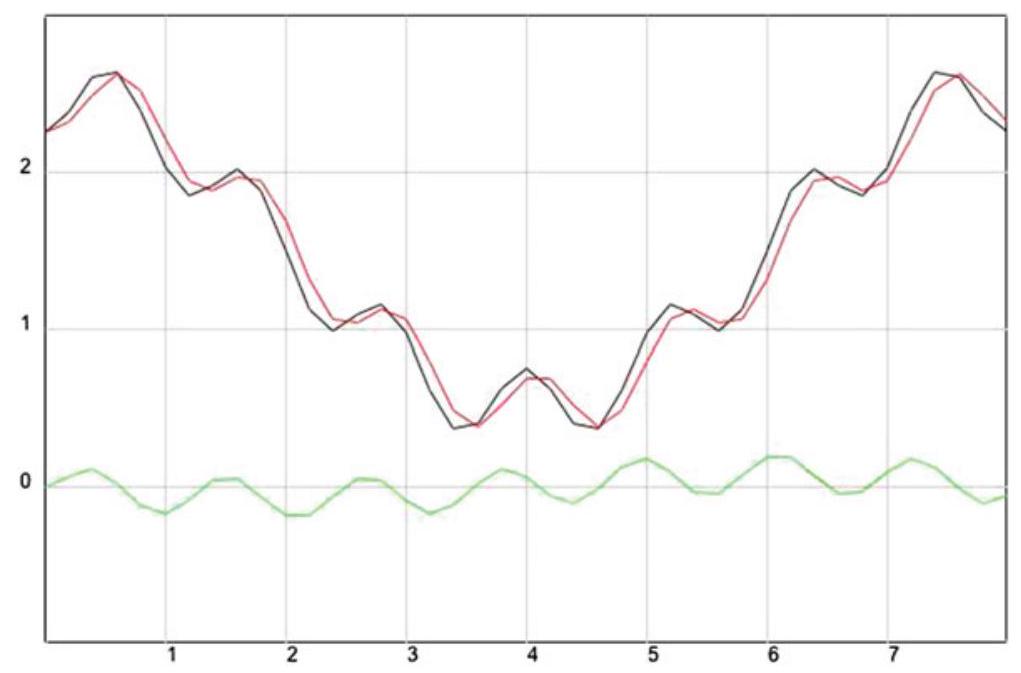

Example

g(t)=\frac{3}{2}+\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{4} t\right)-\frac{1}{4} \cos \left(\frac{7 \pi}{4} t\right), 0 \leq t \leq 8

Sample at t_{k}=k / 5, k=0,1, \ldots, 40

\begin{array}{rlll} \frac{1}{2}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}\right)=y_{2} & \frac{1}{2}\left(x_{3}+x_{4}\right)=y_{4} & \frac{1}{2}\left(x_{5}+x_{6}\right)=y_{6} \\ \frac{1}{2}\left(-x_{1}+x_{2}\right)=z_{2} & \frac{1}{2}\left(-x_{3}+x_{4}\right)=z_{4} & \frac{1}{2}\left(-x_{5}+x_{6}\right)=z_{6} \end{array}

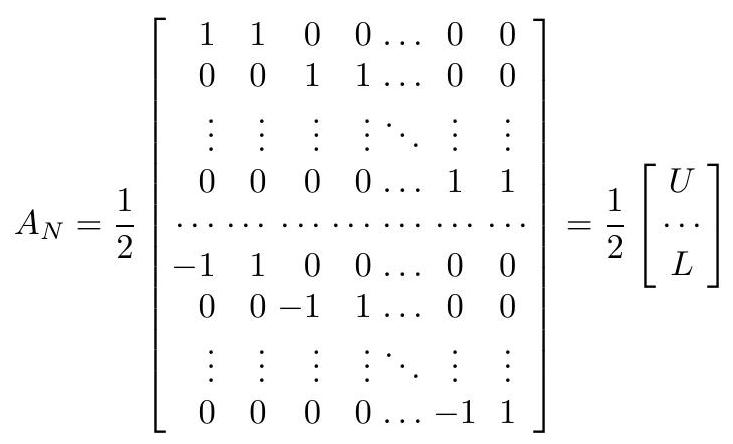

A_{6} \mathbf{x} \equiv \frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{rrrrrr} 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{l} x_{1} \\ x_{2} \\ x_{3} \\ x_{4} \\ x_{5} \\ x_{6} \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{l} y_{2} \\ y_{4} \\ y_{6} \\ z_{2} \\ z_{4} \\ z_{6} \end{array}\right]

Almost orthogonal

\begin{gather} A_{6} A_{6}^{T}=\frac{1}{4}\left[\begin{array}{rrrrrr} 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cccccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & -1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right] \\[10pt] =\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{llllll} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right]=\frac{1}{2} I_{6} \end{gather}

In general,

A_{N} A_{N}^{T}=\frac{1}{2} I_{N}

These matrices are nearly orthogonal.

Haar Wavelet Transform Matrix

Can make them orthogonal by dividing by \sqrt{2}:

y_{k}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\left(x_{k}+x_{k-1}\right), \quad k \in \mathbb{Z}

and

z_{k}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\left(x_{k}-x_{k-1}\right), \quad k \in \mathbb{Z}

W_{N}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\left[\begin{array}{ccccccc} 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & \ldots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & 1 & 1 \\ \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots \\ -1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & \ldots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & -1 & 1 \end{array}\right]=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\left[\begin{array}{c} U \\ \ldots \\ L \end{array}\right]

Moving to 2D

For a 2D image represented pixel-by-pixel in the matrix \mathbf{A}, we can apply the 1D transform to each row and then to each column: W_{m} A W_{n}^{T}

Result ends up in block form:

W_{m} A W_{n}^{T}=2\left[\begin{array}{ll} B & V \\ H & D \end{array}\right]

B represents the blurred image of A, while V, H and D represent edges of the image A along vertical, horizontal and diagonal directions, respectively.